Conversations with Makers is a new series on the blog.

As part of my work I regularly meet makers to discuss their creative practices and I always find the conversations insightful and inspiring. I thought maybe you would too. The act of articulating your work, to another person, regularly, is something we often overlook but which is vital if we are to remain critically engaged with what we do. Discussing your work, but also hearing other people talk about their work, helps the thinking behind the making no end.

So, once a month, I will share a conversation I have had with a maker. First up – Lena Peters.

I met Lena at New Designers this year, and was immediately taken by her ceramic work and the fictional narrative she had created around the pieces. Curious to know more, I invited her to have a chat. When I asked Lena where we should meet, she suggested the British Museum, a place that has had a significant influence on her, and which is one of those places in London I often go just to think. It felt appropriate. The conversation we had touched on the relevance of museum collections to both of us, the influence of history and myth on her work, and the impulse in people to tell stories and to create explanations for the things in life we cannot fathom.

MV Would you say that the BM is a source of inspiration, do you come here to gather ideas?

LP I love the British Museum, because it’s so big and there’s such a wide variety of stuff. This is my favourite place, I love art galleries too, but I get something different from being here.

Are there particular rooms in the BM that you are drawn to again and again?

The Asia section – the Japanese, Korean and Chinese ceramics bit. I really like the Mexico room with the snake and the two-headed dragon…

…I don’t think I’ve been there before- I always find myself in Assyria and the Ancient Near East even when I set out to see something new!

I’ll take you there! You’ll have seen the snake, it’s on a lot of the posters. So that’s a room I really like, along with all the Greek galleries. One of the things I’m really interested in my work is the fusion between human and animal, and the Greeks always do that so well. There’s lots of fantastic things to look at.

And how do you use the museum? Do you sketch or photograph?

For a lot of my research I read. And then I come to the museum to look and think. I do sketch and take photographs, but it depends on where I’m at with the project. Towards the end when I was thinking about the display I came here a lot to see how things were displayed in cases and to photograph the text panels.

You mention reading quite a bit, would you say that it’s a key part of your research process?

Definitely

And is that documents, like historical sources, or fiction?

It’s kind of everything! I work in a bookshop, and I’ve always loved books. If it wasn’t ceramics it would have been creative writing. I read a lot of children’s fiction – I’m a children’s bookseller – and I think that is part of the fun of it, I love classical fairy tales and historical stories.

I’m interested that you describe yourself as “a storyteller who creates illustrative objects which work to embody a narrative” which sounds to me like the material you use could be anything,g although at the moment it’s ceramics. Is that true or will it always be ceramics-based, and it’s the method that is narrative-driven?

I don’t think necessarily it is always going to be ceramics based. I’ve always wanted to branch out into illustration and I’m really interested in textiles as well, with their rich historical background and so many ways to reinterpret (like Grayson Perry’s recent work). So I think it could probably be anything.

It sounds like any material that gives you a surface to work from is important?

Yes, definitely.

Is the surface more important than the 3D construction of objects or are they working together?

It depends, for my figurative work they’re working together, but then for something like the vase-form, I make the most generic vase form, simplified from things I’ve seen here in the British Museum. I didn’t want to just imitate classical form – I wanted to suggest it, but I wanted the simplest canvas that I could have. It’s more about how the 3D form brings the illustration to life not about the form itself.

And, I suppose with you creating a ‘new’ material culture (that’s drawing influences from Roman and Celtic or British) you don’t necessarily want anything that is too obviously one or the other. You’re suggesting that there was a middle ground. The forms have to be echoing things that exist but also being slightly different…

Yes, exactly. And that’s why I chose to hand-build them. People suggested that I throw them, or cast them to reproduce the exact form, but I wanted them to be slightly wonky, I wanted them to have that hand-built quality, not to be perfect or a direct imitation. To be something new.

Ah, I hadn’t realised that. I’d just assumed you’d slip cast them!

No! They’re coiled. All the vases and the figures…

…it’s pretty labour intensive with the hand building and then the surface treatment. Do you put slip on and then remove it?

It depends. Some of them are covered in white slip, to provide the white surface, because I didn’t want to glaze, and then I paint on top in black underglaze. It’s all done free-hand, I don’t really know what’s going to go on them before I paint them.

There’s not a fixed design? I saw on your Instagram lots of sketches and illustrations – you created an entire archaeologist’s notebook- so I’m guessing there is a designed element to the pieces, in that you have imagery in your mind, but you’re coming to it without knowing precisely what is happening…

Yes. I have vague ideas and I do sketches, but it’s more that I have a visual language that works around the project, which can be reconfigured in different ways for different objects.

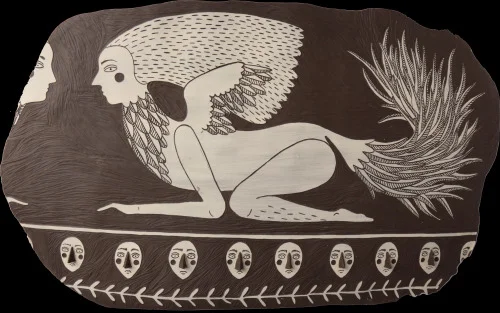

The other objects were in black clay, which I covered in white slip and scraffitoed. All the black areas are carved away and have little lines and are textured…

A bit like a lino cut when bits are left…

Absolutely. And with those it was the same thing, I went into the carving without really knowing what was going to happen, and just hoping!

Was that successful? Did you have things that didn’t work?

Early on I made a sphinx with wings and a woman’s head, and it was a nice figure, but a few weeks before the end I decided that it didn’t fit the narrative because everything else is so based in the English woodland. The making and the narrative develop in tandem, I don’t have the full story at the beginning…

I did wonder if you did more research and illustration to build up that visual language first, and then make, but you’re saying it happens together…

I do a lot of research, a lot of reading when I don’t make, but then the fine-tuning and the way they all fit together happens later. And with this piece it just didn’t fit so I used it as a test piece for glaze!

I’m really interested in your creation of a completely new narrative. For a lot of makers there might be an element of narrative in their work, but not many go as far as creating a completely fictional timeline of things that might have been, that have only just come to light. How did this come about, the desire to create a new object language?

I’ve always been really interested in mythology and fairy tales. My Dad, especially, has always been interested in history and my Mum in stories, so they met in the middle. It meant that on family holidays I’d be dragged around churches and museums, and so I love looking at old things. And I wanted to create stuff that told stories, but I was making these objects and I wasn’t sure how I was going to do it. I wasn’t sure if I was going to market them as a design piece, or something that could be reproduced, I was dithering quite a lot, because I really didn’t know where I fit. And then, out of talking about speculative design, and creating fake realities or objects from a fictional universe or narrative, I was encouraged to just do it – to go all out. It was something I had been on the edge of doing the whole year…

Why do you feel you had been on the edge of it? What was it about that way of working that made you reluctant to take the plunge?

I was on a ceramic design course. Which isn’t to say they weren’t open to all kinds of practice, but it was very design-focused. I felt like I should be doing that kind of work, but in third year it was the chance to develop what we wanted, and this collection felt like it was going in a fine-art direction, so that was the direction I went in. It was more interesting to me than creating products

I can see how these could be products, in that there are makers who do historically-based work, that references traditional techniques or uses historical sources but takes them in a completely different direction. But I feel that having an entire world around them, as well, you can engage with them on that level. So, in addition to the objects being beautiful and fascinating, there is this intriguing story, and I love the fact that it makes you question: ‘is this real? Did this really happen? How did I not hear about it? Surely it would have been on the news!’

I think that the way you presented it was just right. You could have said ‘this is fiction, it is a story’, and people could think ‘oh well, that’s just something you’ve added on top’ but I like the way it was left quite vague, and I was left thinking that these objects probably should be in a museum, and why weren’t they?

I really enjoyed that element of it. In my final presentation I presented it as if I were the archaeologist, giving a museum tour, and then I switched back to me to discuss the making of the work. It was fun. At the degree show, and at New Designers, I gave parts of that speech to visitors and they would say ‘so…where did you find them?’ and a lot of people thought maybe I was an archaeologist before I did this degree. And I had to say to them (whispers) ‘no, I made it all up!’ (Laughs)

I had to explain it a lot, which I really enjoyed. That element of uncertainty was what I was going for with the project; I wanted people to have that moment of ‘are they/aren’t they’.

Do you feel like that’s something you’ll continue to explore –the uncertainty within a narrative – or are you interested in storytelling in general?

I’ve been thinking about new projects, very vaguely. I’m interested in religion and ritualistic practices, and I’ve been looking at the occult and witchcraft. And there are so many ways that objects have been used to suggest ritual or created for ritual purposes. So maybe it’s just a step further that you are able to interact with these objects…

It reminds me that when I studied archaeology at university it was a bit of a running joke that if you didn’t know what something was it was ritualistic. It was a kind of catch-all, ‘we don’t know how to classify this at the moment so we’ll just say: ritual!’ Ambiguous objects get put in that category until they get moved into something else, or they stay there and we never really know what they are for. I think ritual is a ripe field for someone interested in uncertainty and objects and history, because it offers the potential for you to make anything you want, so long as there’s enough to hold it to something…

…enough to make you suspend your belief for a second.

There’s a quote in a book called Speculative Everything, about speculative design, which says (and I’m paraphrasing really badly) ‘when we see strange objects we immediately question what kind of society produced them’. And that’s what I was interested in with this project. I wanted to give some background information, and the story did that, it gave you a narrative arc, but people still looked at it and asked ‘what’s that for?’, ‘why have they got holes in their heads?’

They were still reacting to the objects more than the fictional story?

Yes, it gave them a framework to fill in the gaps for themselves. And that’s what I want to keep doing, that the objects are a prompt for people to think in different ways.

These fictional, narrative-driven objects allow people to look at them from different aspects, and to engage with you. Like any kind of author, you’ve got a lot of knowledge in your head about this world, this narrative that you’ve created, that people might never find out. But it’s there, and if they wanted to, it could inform how they see the collection…

Yes, but I didn’t need them to know. They could pick up the booklet and find out, but if they didn’t want to read it the objects had a sense of mystery by themselves.

So, you’re saying the narrative you were creating – the alternative history – it wasn’t so vital for people to hear it. But was it important that they acknowledged it was there?

Yeah. There was an introductory paragraph, but after that it was up to them how far they wanted to engage with it. How much detail they wanted. And I went into a lot of detail about the excavation, the people involved… but if they skim read it they’d have a different sense.

It’s a bit like how objects are interpreted in museums. There will be a text panel or label with the general information, but there could be layers and layers of information, for people who really want to know more, either in gallery texts, books or digitally. But for most people that cursory engagement is enough, a quick look around. It does feel to me that you are working a bit like you are a one-woman museum. You are creating the culture, the material, the narrative, and then you are presenting it. It’s your own interpretive space.

Did I tell you at New Designers that I displayed it like a museum at the degree show? It had a Perspex case and little panels of information. And there was a pillar where my display was, which to me just suggested British Museum. And that helped create the space. That was part of the fun. I answered an email the other day about crossing boundaries in my work and how it’s illustration, it’s clay, it’s storytelling but it’s also installation. And that is unexpectedly important to me, the way it is presented.

I was going to ask you about that. Now that the work is going out into the world at shows. How important to you is it that it’s displayed in a certain way? Are you happy for the objects to be split up, and that context lost?

I think the context is really important. But I think it matters less now that they have been shown as a group, and they’ve been established as a collection. If you look at museums they loan certain objects to be part of different things…

…I like that – they’re on loan…

yes, so it’s like they’re on loan from a bigger collection. And they are going off all over the place: I won the UK Young Artists prize at New Designers and a few of the objects are going off to Korea and then the show in Nottingham next year. I’m also showing at the BCB Fresh exhibition and in CSM’s Lethaby Gallery as part of the Creative Unions graduate showcase. So they will be split up, but still in small groups rather than single pieces, which makes a difference as they will still relate to each other. They’ll create enough of a community for it to be ok.

And, because I have the catalogue with the narrative in it, there are images of all the work and descriptions of everything. So even if people only see a couple of pieces they will still know that it was part of a larger collection, and there is that context.

You told me how this collection comes from locations where you grew up, that informed you, and I was wondering in terms of developing new work, do you think you’d be interested in responding in a site-specific way to places you are less familiar with? Or do you think you’ll always come back to places that feel slightly more like home?

Its’ something I’ve thought about – I do think it would be really interesting to do site specific responses. And as long places have a storytelling or historic aspect then I am always really inspired by things connected to the land, and that mythology. I suppose it’s because I grew up in Sheffield, in the Peak District, so that’s where my passion lies specifically – I’m drawn to those kinds of tales, of magic and woodland sprites. It would be an interesting way to challenge myself, to see what I could come up with if I was removed from that familiar area.

It feels to me that maybe this methodology you have developed would be interesting to explore through residencies: going to a new place, finding the stories that exist and building new elements

Yes, I think that could work, if the place really inspires me. There are lots of places in the north of England, and I love the folklore of Scandinavia, so I know those sorts of places would hold lots of interest for me.

Is there a context that you feel definitely isn’t for you?

Maybe anything that was purely historical. There are places I find interesting and they are full of history, but if there isn’t an element of myth or that element of uncertainty I’m not sure I’d want to respond to that. It’s interesting to respond to a historical site, but because it’s rooted in known fact and reality I feel I would lose something there.

So, really, it is about uncertainty, and that gap that you can inhabit, where you’re not quite sure what it is…

…and it means I can fill it with whatever I want!

Yes, if you’re just responding to known historical things there is the possibility for people to judge the accuracy of it, but if you’re asking ‘what is myth, what are stories?’ they are human ways of dealing with the unknown, of creating things that we can understand, about something we can’t control…

And they are truths in their own right. They exist to talk about truths that we can’t articulate in any other way, and that’s something I find fascinating.

So, a residency in a historic house where there are quite definite limits, and things are known, might not be your thing…

But, then, if the house was in a village which had a yearly harvest tradition, that would change the context completely. It would give me a new angle. I think that in most places you would be able to find something…

Yes, there is always something lurking! Iwas fascinated for a while by the things left inside houses when they are being built, like mummified cats and shoes, deposited there to ward off evil spirits. I used to work at the Pitt Rivers Museum, and there were lots of objects like this in the collection. I used to wonder about who put them there. Because they were placed there with intent, and often not even by the people who would live in the house, probably by the people building the structure, who are sticking iron nails in mice and shoving them in gaps thinking ‘this will keep us safe’. There must have been some reason behind it, but these things don’t necessarily come to us through time, and they might have been incredibly locally based – it’s not even that all across the country a shoe means the same thing, and that’s what I found fascinating: the meaning could have been completely specific to that one person, and we may never know what that was. It leaves us space to wonder ‘well, what could that be?’ and if we can’t figure it out we make up a story and put it in a display case for other people to think ‘how weird’.

Some of these things were only oral traditions, that aren’t recorded, you look at them and go ‘why?’.

Before I worked at the museum I wasn’t as interested in these things, but I have become a lot more interested in our national traditions and rituals. In the UK we do have quite a lot of traditions that we just don’t observe that much and are now oddities, I suppose, like Morris dancers. But at one time they would have been an everyday thing, and everyone would have understood what it was about, and respected it. I find it interesting how there are pockets of the country where these traditions have been maintained, but so many have been lost. I’m not sure there are any ‘British’ traditions that I uphold anymore. I think the Harvest festival at school was probably the last one!

In part, one of the things that I explored in this project was that this island has been invaded so many times, and the roots of all these traditions are in so many different places, and there’s no collective national identity to grasp onto in the same way. And maybe it has something to do with moving away from the countryside to the city – as soon as lose the connection with the land, because so many of the traditions are related to farming, you automatically lose the traditions. Midsummer and midwinter become less important. Even in the places that hold onto these traditions – how much of it is to do with it just being a fun thing to do, how much of it is belief?

I would imagine that some of the belief aspect has dwindled, and it’s a case of ‘we do this because we do this’ it’s a community activity, it’s a social activity. Not so much the belief that if we don’t do these things then the harvest will fail or the sun won’t return in spring. But, even maintaining those community ties is a very important function, now. But I do wonder what we’ve lost by not maintaining some of these traditions.

It’s a massive field, which does make it very exciting for you, at the start of your career, if you want to continue to explore these things…

Yes, there always stories, there’s always things to tell. Something you just reminded me of, is the novel American Gods by Neil Gaiman. The ideas in there, about cultural exchange and of bringing beliefs to new places and the way they change and interact. And also about the new gods that we have. The way that belief gives things power, but how you can take away power if you stop believing in something. So, like with the traditions – people may not believe anymore that if they don’t do it the sun won’t come up- but there might be a superstition, and element of doubt in the back of their head that ‘this has been done for years’ and what would happen if it wasn’t done?

At the moment, are you continuing to add to the current collection or is it staying as it is for display?

I’ve made a couple more pieces. I felt I needed to make them because the way they collection had been split, I was left with one group that the balance was off, so I created new pieces to address that. Visually there wasn’t enough of the painted pieces, and it just didn’t feel right. But apart from that I think it will stay as it is. I’ll never be in my third year of uni again, when I’m panic-producing and working towards the degree show. I’m not sure I’d be able to make more work that fits into how that work was produced, and have it feel right.

It feels like a collection with a beginning, a middle, and an end… do you feel ready to move onto a fresh story?

I think it’s important to keep moving forwards, otherwise you could just keep adding and adding to existing work. I think it’s important to keep developing your practice and your thinking.

Do you have inklings of where it might go?

I’m really interested in ritual, recently I read an article about shamanism in modern art practice and how that’s used in all sorts of different practices. I’m not into that whole thing – I won’t be taking hallucinogens and seeing what happens – but what if I was to create objects for a ritual of my own, what context would that be, how would they fit into that?

That sounds to me like you could become an active part of the work, as well, rather than just the author/creator. I know at your degree show you were assuming the role of the archaeologist, but do you feel you’d like it to become more overt than that? Could this lead to performance? Could this lead to a collection where you embody a certain spirit, and you use the objects? Or is this a step too far?

Funnily enough, I always thought that would be a step too far. Even the thought of it fills me with dread, it’s not really my comfort zone. But the more I think about it I do wonder if that’s the logical end point, especially for the things I’m thinking about right now. And there would be ways around it, I could always work with video!

Lena Peters is a London-based storyteller whose Sheffield upbringing nurtured her passion for history and nature. These elements combined with her interest in folklore and mythology mean that her work dances between the real and the unreal, creating illustrative objects which work to embody a narrative.