It is often around this time of year that I feel a slight shift, as the daylight is in short supply and winter feels close at my back. I notice that I switch from feeling full of energy for being outside, and doing things, to wanting to hibernate. I resist this temptation for as long as possible, but experience tells me that I will eventually succumb and it will be hard to muster the motivation for more than the bare essentials of living and working. Luckily the weather here in London at the moment is incredibly mild and the sun, when it’s out, is still golden and glorious, so I don’t need much encouragement to be out in the world. But I can feel it, waiting. And it’s got me thinking about this tendency to draw in, to hold on to things, to save stuff.

I don’t think anyone would argue with the impulse to squirrel ourselves away in winter, to stay cosy and enjoy the benefits of central heating and twinkly lights. But, what about when that desire to curl up starts to permeate into other areas of your life, like your work or your creative practice? What then? Where is the balance between healthy, natural protective behaviour (like retreating in winter) and things that don’t help at all?

When I was little my hobbies were all craft-based and I’d get given sets for making and doing all sorts of cool stuff (candles, soap-making, marbling etc) which I loved. But every now and then I’d be given something really nice like a set of fancy colouring pencils or paints, and I couldn’t use them. They felt too nice, too special to use on ordinary, messy, play. I saved them, a bit like my Granny who had tea cups ‘for best’, and waited for a time when I had an activity that deserved such lovely things. But those times never came, and my ‘special’ materials sat untouched, laden with guilt. I continued this behaviour long into my teens and 20s, mostly with notebooks – I’d impulse buy the most beautiful things and then not have the confidence to write in them, preferring to do my scribbling in craft-paper notebooks or school exercise books. Again, there was this impulse to save things, to have to have something important or worthy to do with them. (I’m going to gloss over the obvious field-day a therapist would have with this story. I can just hear the question now “and why did you think you didn’t deserve to use these nice things…” let’s not go there today, ok?)

It’s only recently that I realised that although I’ve managed to learn to be ok with using nice things for ordinary purposes (life is too short!) I have been applying this same mentality to my creative practice. I often find myself having ideas or an impulse to write/make something and I convince myself that it would be better to do it later, when I have enough time, or when I feel right, or I’ve done some more research etc etc. I scribble notes to myself in books and hope that the kernel of something will survive and be waiting for me when the time comes. Which it never does. And I know this. But, I think this too, like hibernating in winter, is a defence mechanism of sorts. By holding things back, by not letting go and acting, there is no risk, no possible disappointment or failure. That is what the part of my brain that only wants good, safe things to happen to me believes. Only, it’s bollocks. There is failure – I’ve failed myself by not doing the work I need to do, by not creating the things I am driven to start. It’s much worse.

When I read Annie Dillard’s The Writing Life recently I underlined a paragraph that felt so appropriate to how I’ve been feeling about this:

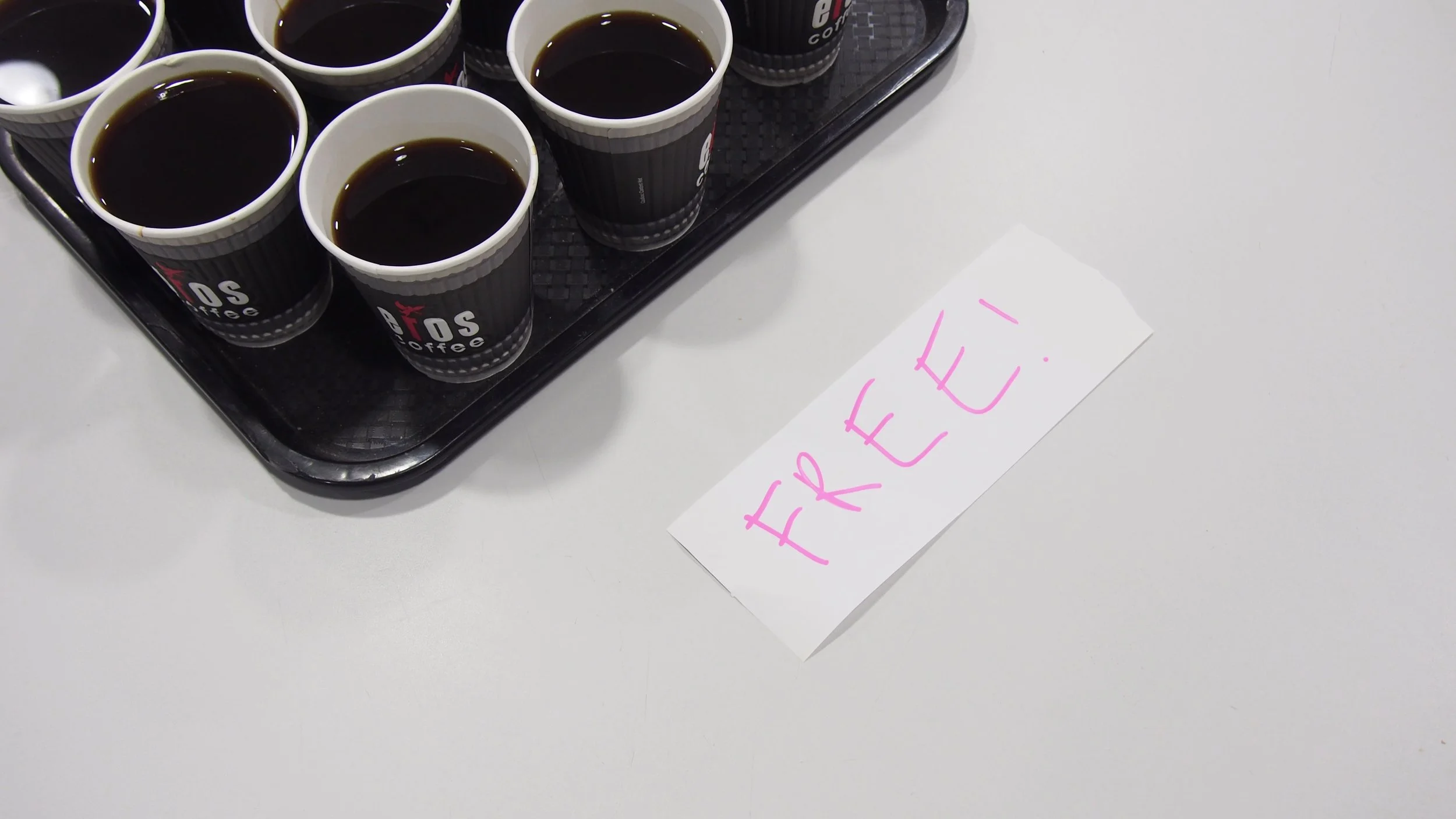

One of the few things I know about writing is this: spend it, shoot it, play it, lose it, all, right away, every time. Do not hoard what seems good for a later place in the book, or for another book; give it, give it all, give it now. The impulse to save something good for a better place later is the signal to spend it now. Something more will arise for later, something better. These things fill from behind, from beneath, like well water. Similarly, the impulse to keep to yourself what you have learned is not only shameful, it is destructive. Anything you do not give freely and abundantly becomes lost to you. You open your safe and find ashes.

This is exactly the sort of thing that should be painted on the walls of education establishments, so that everyone is reminded, daily, of the profound importance to creative people to use their creativity, to give freely of the ideas and skills they have, to act. I have stuck this on a post-it on above my desk to remind me that the next time I get that itchy feeling of an idea forming, not to resist it but to do something about it, take that first step, no matter how small or how imperfect it may be.