I have talked before, in this space and more widely, about how I am a maker who does not make things. For a number of years, it has been a sort of existential issue for me, especially since I spend my time surrounded by makers and other creatives. The feeling of unease about not having a making practice, despite still identifying as a ‘maker’ and having a maker’s sensibility in the world, is strong.

Recently these issues have died down a bit, have been less painful. Is it that I have found a resolution, a way to live with the non-making paradigm? Or is it that I have enough happening in my other work – with people, with words – that the making-shaped hole isn’t so big? I don’t really know. I found myself saying to someone the other day that I wasn’t sure I was ready to make anything until I fully understood why I was making it. Not what I was making, but why I was making it. Because I felt that any un-thought-about making would be irresponsible on my part. I feel uncomfortable creating more stuff unless I know there is a good reason for it.

Which brings me right into the awkward part of this discussion. For me, there is currently a fundamental problem with ‘making’ as a creative act. I have deep concerns about its effects on people and the planet, things we do not see directly but have a hand in. This is disquieting and unsettling for me – I work to support the creative practice of others – and I realise that I must live in a world of cognitive dissonance for most of the time. But today I want to articulate these concerns I’ve been having about the sector I work in, because it no longer feels like an option, something that only some people should engage with. Creating work in a responsible manner is everyone’s issue.

Ten years ago, I made the decision to shift from being a serial craft hobbyist into someone who engaged with creativity as her profession. I went back to college to do an art & design foundation course and then to university to do a BA contemporary craft course. Those experiences have been wonderful, have opened me up to so much possibility, to amazing people, and have ultimately led me to work that I love, in a sector I care deeply about. But I was disturbed by the volume of waste I saw in those education establishments. I am still haunted by memories of skips full of wood, plaster, textiles, all sorts of detritus, but also full of ‘artwork’ that was only recently up in someone’s studio space being assessed, or on show. So quickly forgotten and binned.

These courses, being predominantly 3D-focused, generated a lot of work, as well as associated tools or equipment (like moulds, screens, jigs) and so many tests or samples. Bits that once they had served their purpose for one short project went on to have no life at all. In the last 10 years, I have moved house four times, so I’m acutely aware of how much stuff I had to deal with from uni and other making. There are boxes of plaster moulds, jars of dye, hundreds of glaze samples that I just don’t know what to do with, and so live in stasis at my Dad’s house. It’s only delaying the inevitable.

This production of things that are ultimately destined to be waste didn’t seem to be addressed anywhere. Yes, there were recycling bins in studios and a few freecycle places you could leave bits for others to take, but ultimately we were left to it, and no one talked about it. I really hope things are different for students now. But the issue of waste by-products in the creative process is only a small part of what I have become concerned about. I am worried that we don’t have enough conversations about materials and about the burden of creating objects that go out into the world.

I think about making as an act that engages with materials and material processes first and foremost. Makers love their materials, and what can be done with them. I love that too. So it’s incredibly hard for me to say that I don’t believe that materials are a benign part of a making practice. They are not inert, magical raw materials; they come with their own baggage. But this is something that isn’t talked about much in some craft disciplines.

The impact of mining and processing metals on human life and on the environment is well-known. I love that contemporary jewellery and metalsmithing is trying to make people aware of this. What if other materials were similarly viewed? I think it is easy to say ‘I work with wool (or clay), which is a natural material’ and expect that to be enough. Both these materials, in the form you buy them from suppliers, are heavily processed, industrial materials. Unless you process the wool yourself, or dig the clay from the ground, it is not an entirely natural material.

It’s not just whether the materials are or can be recycled, or whether they come from sustainable sources: It’s the hidden aspects of the processing or creating of materials that need to be made known. There should be more transparency on the processing of ‘raw’ materials, so that makers can make an informed choice about what they use.

There is also the issue of the longevity of materials, of what will happen to them at the end of an object’s life. It’s reasonable to question how much of a product we buy in shops can be re-used or recycled at the end of its life, saving it from landfill and reintroducing it into the production of other things, so why isn’t it reasonable to question craft objects similarly? Should makers consider how easily their work can be reused, repurposed or recycled? Already, just by asking that question, I feel on shaky ground – does this not just reduce hand-crafted objects into products, like the mass-produced things we buy? In some ways, yes. We are holding manufacturers to higher standards, so why not have the same expectations of makers? But, that feels transgressive: The act of creating crafted objects somehow feels exempt from this discussion. Why is that?

My background is in Archaeology and Ancient History. With this training, I worked in Museum Education for many years. At work, I was surrounded by objects that people had made in the past, objects that had survived. It’s wonderful. I am still amazed by the power of objects to outlive their creators, their users, for so long. The stories contained within objects drew me to studying the past in that way; the things we can learn from them and the physical connection to other people’s hands and ideas. The feeling of seeing another person’s fingerprints in a clay object, and placing your own finger in the hollow.

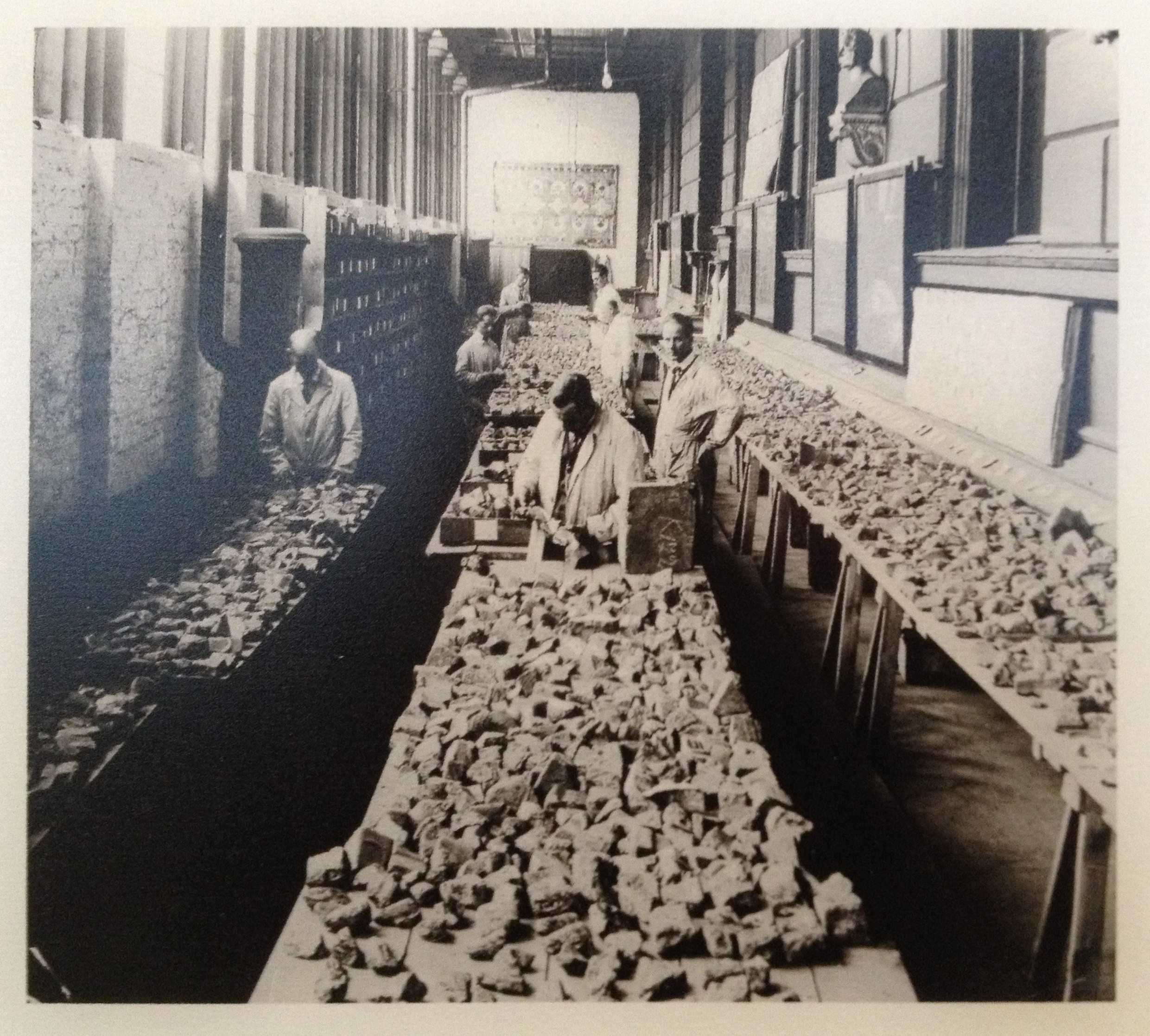

All this just reminds me of how everything we make has the potential to be around for a very long time. Today’s things are the archaeology of the future. I once excavated an industrial kiln on a Roman site in Italy. We dug up tonnes of terracotta tiles before we could see the kiln structure, intact, almost 2 metres down. My overriding memory of that summer was of sorting the tiles into the three main types and weighing bag after bag, keeping records of the stuff we found. I was overwhelmed by how much there was.

Working in museums gave me a different sense of time when it comes to objects. Not only how long things have survived but how long they will continue to survive. Museums take responsibility for objects indefinitely, forever, to conserve and share our material culture for as long as possible. It is incredibly hard, almost impossible, to dispose of objects, because of this responsibility to safeguard the objects for the future. I wonder what it would be like to take this view of the objects we buy for our homes, or as gifts for other people, the stuff we surround ourselves with. It feels like an impossible thing – who could like or need something forever? But this idea interests me. What if we, as makers, asked the people who buy from us to treat our work like museum objects? Would it be unreasonable for us to ask for our work to be used and treasured for as long as possible? That they would not be disposed of easily? What would those conversations be like? It’s something that artist Claire Twomey engaged with in her 2010 project Forever:

“This work was made in response to the historic Burnap collection at the Nelson Atkins Museum in Kansas, USA; the collection comprises 1345 objects and one of these, the Sandbach Cup, was chosen by the artist and reproduced 1345 times with the help of Hartley Greens & Co. Leeds Pottery, a ceramics factory in northern England.

The public were able to own one of these cups if they agreed to sign a deed from the Museum that stated they would keep it forever: 10,000 people signed this agreement highlighting issues of ownership, responsibility and the notion of time.” www.clairetwomey.com

This situation fills me with a kind of awkward dread. How do we have a conversation with someone who wants to buy our work about what they intend to do with it? How does that discussion not end up sounding preachy or distrusting? We cannot tell people what to do, but we can share our own hopes about what might happen to our things once they are out in the world. By sharing our own ideas of owning craft, our audience or customers can engage with that, and possibly make different choices.

We can think about making in a simple way – we use materials (input), transform them through skill (process) into objects (output). Along the way, we produce by-products that may be essential to the process but ultimately have no other function and so can be considered waste. We need to be critical of our own practices, regarding all 4 of these elements, holistically. We should not focus on one in isolation and ignore the rest.

I would love to hear more makers talk about the things they have observed about their own material choices, technical processes, waste, and final work, and ways they are trying to create more responsibly. Small steps, little changes, things that might make a difference.

I am aware that in raising this issue, and sharing my thoughts, it can quickly tend towards the didactic. I don’t want to tell people what to do, or to make people feel bad about what they do. There is no judgement here, but I do believe we have a responsibility. No one needs us to make things, it is not essential. It is a wonderful, enhancing addition to life, but it is a choice. By consciously deciding to create things, we are adding to the world, and we ought to respect it enough to do this in as harmless a way as possible.

Note:

I admit that I am under-informed about these issues. Most of my concerns come from my personal experiences and observations, which are limited.

I would love to know more. If you are a maker whose work engages with these issues directly, or you have made active changes to your practice, please get in touch – I’d love to learn about what you do.

If you have any suggestions for things I can read, watch or listen to that relate to these issues in a making context, do let me know.

Pretty nice post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wished to mention that I’ve really loved browsing your blog posts.

In any case I’ll be subscribing in your feed and

I am hoping you write again soon!